Affiliate Marketing vs Advertising: Key Differences Explained

Discover the main differences between affiliate marketing and advertising. Learn about performance-based vs direct advertising models, cost structures, and whic...

Understand the critical differences between affiliate associates and subsidiary companies, including ownership structures, control levels, financial reporting, and legal implications for your business.

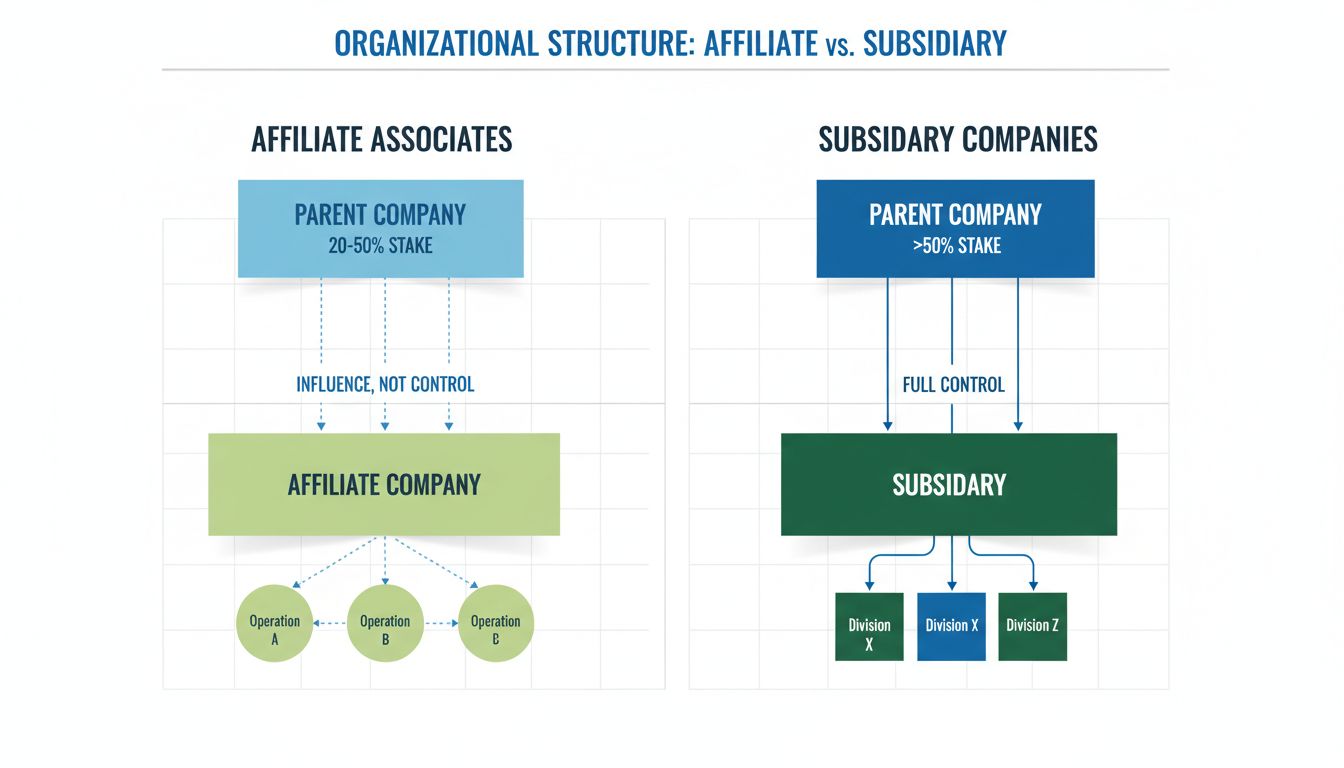

The main difference is the parent company's level of ownership. Subsidiaries are majority or wholly owned by the parent company (>50%), giving the parent significant control, whereas affiliates have only a minor share controlled by the parent (typically 20-50%), retaining majority control themselves.

The distinction between affiliate associates and subsidiary companies represents one of the most fundamental concepts in corporate structure and business relationships. While both terms involve one company having a stake in another, the level of ownership, control, and legal implications differ significantly. Understanding these differences is crucial for businesses planning expansion, managing investments, or structuring their organizational hierarchy. The choice between these two models can have profound implications for financial reporting, tax obligations, liability protection, and operational autonomy.

The primary difference between affiliate associates and subsidiary companies lies in the ownership percentage held by the parent company. Subsidiaries are defined as companies where the parent company owns more than 50% of the voting stock, which grants the parent company majority control and the ability to make unilateral decisions regarding the subsidiary’s operations, strategy, and management. This ownership threshold is critical because it crosses the line from influence to control, fundamentally changing the parent company’s relationship with the entity.

Affiliate associates, by contrast, involve minority ownership typically ranging from 20% to 50%. This ownership structure provides the parent company with significant influence over the affiliate’s operations and strategic direction, but it does not grant the parent company control. The affiliate retains majority control in the hands of other shareholders, meaning the parent company cannot make unilateral decisions without the consent of other stakeholders. This distinction creates two entirely different business relationships with vastly different implications for governance, financial reporting, and strategic alignment.

The ownership threshold of 50% is not arbitrary—it represents the legal boundary between control and influence. When a parent company owns exactly 50% or less, it cannot force decisions through voting power alone. When it owns 50.1% or more, it can. This single percentage point difference creates a fundamental shift in the parent company’s ability to direct the subsidiary’s operations, appoint board members, and determine strategic priorities.

The level of control exercised by the parent company represents perhaps the most significant practical difference between these two structures. In subsidiary relationships, the parent company exercises substantial operational control because it holds the majority of voting shares. This control manifests in several concrete ways: the parent company can elect the board of directors, determine major strategic decisions, set operational policies, and direct the allocation of resources. The parent company can essentially run the subsidiary as an extension of its own operations, though the subsidiary maintains its separate legal identity.

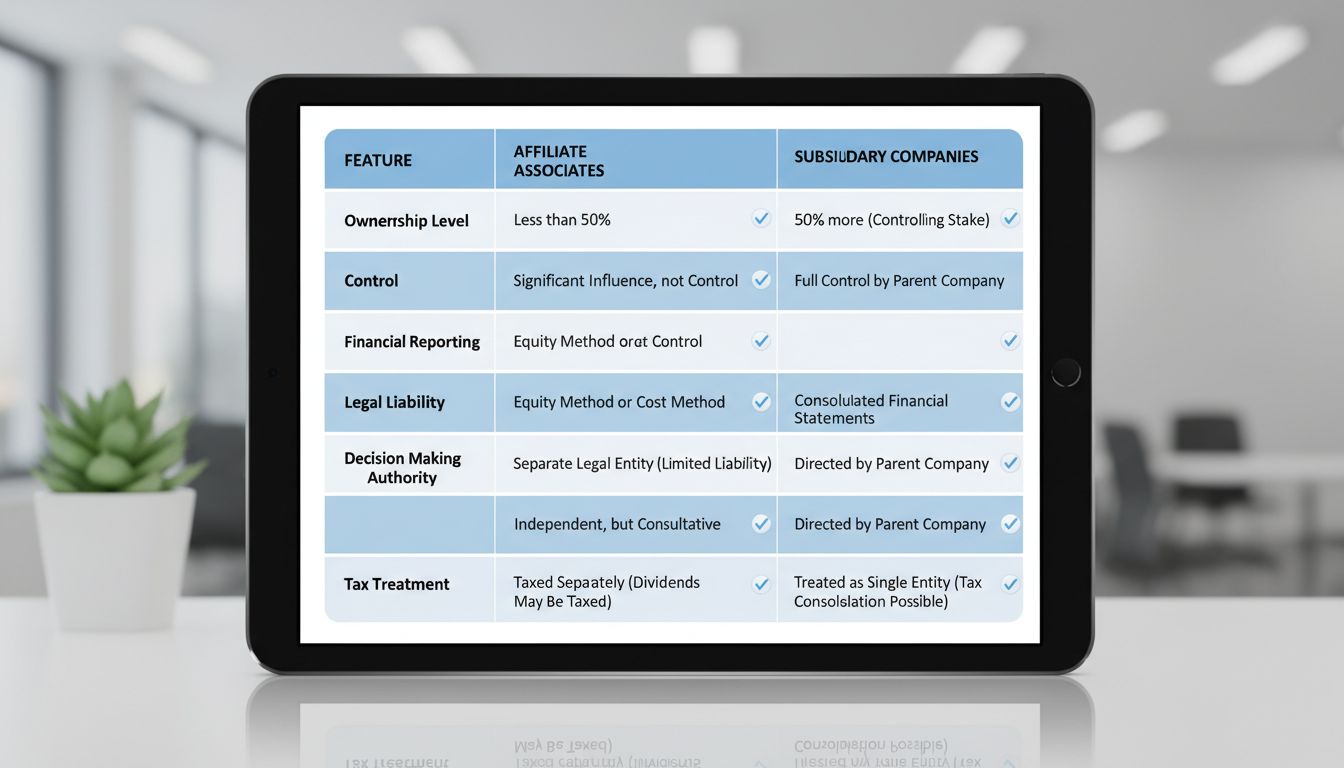

In affiliate associate relationships, the parent company has influence but not control. While the parent company can advocate for certain strategic directions and may have representation on the board of directors, it cannot force decisions unilaterally. Major decisions require consensus or majority approval from all shareholders, which means the affiliate’s other shareholders have equal or greater say in the company’s direction. This creates a more collaborative governance structure where the parent company must negotiate and build consensus rather than simply dictate policy.

This distinction has profound implications for how quickly decisions can be made and how aligned the affiliate’s operations are with the parent company’s overall strategy. Subsidiaries can move quickly to implement parent company directives, while affiliates may move more slowly due to the need for consensus-building among multiple stakeholders. However, this slower decision-making process in affiliates can also provide benefits, as it ensures that decisions are thoroughly vetted and that minority shareholders’ interests are protected.

The financial reporting requirements for subsidiaries and affiliates differ substantially, reflecting their different levels of control. Subsidiaries’ financial results are typically consolidated into the parent company’s financial statements, meaning the subsidiary’s assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses are combined with the parent company’s figures to present a unified financial picture. This consolidation is required because the parent company’s control over the subsidiary means it has effective control over the subsidiary’s financial resources and performance.

Affiliate associates’ financial results are not consolidated into the parent company’s financial statements. Instead, the parent company records its investment in the affiliate as an asset on its balance sheet and uses equity accounting to record its share of the affiliate’s profits or losses on its income statement. This approach reflects the parent company’s lack of control—since the parent company cannot direct the affiliate’s operations, it cannot claim to control the affiliate’s financial resources, so consolidation would be inappropriate.

The consolidation requirement for subsidiaries creates more complex financial reporting obligations. The parent company must eliminate intercompany transactions to avoid double-counting, adjust for intercompany profit margins, and present minority interests separately when the subsidiary is not wholly owned. These consolidation adjustments can be substantial and require sophisticated accounting expertise to execute correctly. Affiliate accounting, while still requiring careful tracking, is generally simpler because it involves recording the parent company’s proportionate share of the affiliate’s earnings rather than consolidating all of the affiliate’s financial details.

One of the most important practical differences between subsidiaries and affiliates concerns legal liability and risk isolation. Subsidiaries provide significant liability protection for the parent company because they are separate legal entities. If a subsidiary incurs debts, faces lawsuits, or experiences financial difficulties, the parent company’s liability is generally limited to the amount it has invested in the subsidiary. Creditors of the subsidiary cannot pursue the parent company’s assets, and the parent company is not responsible for the subsidiary’s debts or legal obligations. This liability isolation is one of the primary reasons companies establish subsidiaries—it allows them to pursue risky ventures or enter uncertain markets while protecting the parent company’s core assets.

Affiliate associates provide even greater liability protection for the parent company because the parent company’s stake is smaller and its involvement is more limited. The parent company’s liability is limited to its investment in the affiliate, and it has no responsibility for the affiliate’s debts or legal obligations. However, because the parent company has less control over the affiliate’s operations, it also has less ability to influence the affiliate’s risk management practices. This creates a different risk profile: the parent company is protected from the affiliate’s problems, but it also cannot directly control the affiliate’s behavior to prevent those problems from occurring.

The liability protection provided by both structures is not absolute. In rare cases, courts may “pierce the corporate veil” and hold the parent company liable for the subsidiary’s or affiliate’s debts if the parent company has engaged in fraud, commingled assets, or otherwise abused the separate legal entity structure. Additionally, if the parent company provides personal guarantees for the subsidiary’s or affiliate’s debts, the parent company becomes personally liable regardless of the separate legal entity structure. These exceptions are relatively rare, but they highlight that liability protection is not automatic—it requires maintaining proper corporate formalities and avoiding fraudulent conduct.

The tax treatment of subsidiaries and affiliates differs significantly, creating different opportunities for tax optimization. Subsidiaries can potentially benefit from consolidated tax returns, which allow the parent company to offset the subsidiary’s losses against the parent company’s profits, reducing the overall tax burden. Additionally, subsidiaries may be eligible for different tax rates depending on their location and industry, and the parent company can structure intercompany transactions to optimize the overall tax position. However, these tax benefits come with increased complexity and compliance obligations, including transfer pricing documentation requirements that ensure intercompany transactions are conducted at arm’s length prices.

Affiliates are typically taxed separately from the parent company, with each entity filing its own tax return and paying taxes on its own income. The parent company records its share of the affiliate’s earnings on its own tax return but does not consolidate the affiliate’s financial results. This separate taxation approach is simpler in some respects but may result in higher overall tax burdens because the parent company cannot offset the affiliate’s losses against its own profits. However, the parent company may be eligible for foreign tax credits or other tax benefits depending on the affiliate’s location and the nature of the investment.

The tax implications of the subsidiary versus affiliate choice can be substantial, particularly for multinational companies operating across multiple jurisdictions. A company might choose to structure an investment as a subsidiary in a low-tax jurisdiction to minimize overall tax obligations, or it might choose to structure an investment as an affiliate to maintain operational independence while still benefiting from the investment’s returns. Tax planning considerations often play a significant role in determining whether a company will structure a new investment as a subsidiary or an affiliate.

Subsidiaries typically maintain operational independence while remaining subject to parent company strategic direction. A subsidiary operates as its own legal entity with its own management team, board of directors, and operational policies. However, the parent company, as the majority shareholder, can influence or direct the subsidiary’s strategic decisions, capital allocation, and major operational choices. Many subsidiaries maintain their own brand identity and operate in distinct markets or business segments, which allows them to maintain customer relationships and market positioning while benefiting from the parent company’s resources and strategic guidance.

Affiliates maintain greater operational independence because the parent company lacks control. The affiliate’s management team makes operational decisions without requiring parent company approval, and the affiliate can pursue strategic directions that differ from the parent company’s overall strategy. This independence can be valuable when the affiliate operates in a different industry or market segment where the parent company lacks expertise. However, this independence also means the parent company has less ability to ensure that the affiliate’s operations align with the parent company’s values, standards, or strategic priorities.

The choice between subsidiary and affiliate structures often depends on how much operational independence the parent company wants to maintain. If the parent company wants to closely manage the investment and ensure alignment with its overall strategy, a subsidiary structure is more appropriate. If the parent company wants to maintain a more hands-off approach and allow the investment to operate independently, an affiliate structure may be preferable.

Understanding these concepts becomes clearer when examining real-world examples. Alphabet Inc. operates Google, YouTube, and Waymo as wholly-owned subsidiaries, which allows Alphabet to maintain complete control over these entities’ strategic direction while keeping them as separate legal entities for liability and operational purposes. This structure enables Alphabet to pursue diverse business strategies across different industries while protecting its core assets from risks in experimental ventures like autonomous vehicles.

Meta (formerly Facebook) acquired Instagram and WhatsApp as subsidiaries, maintaining their distinct brand identities while consolidating their financial results and integrating their technology platforms. This subsidiary structure allowed Meta to preserve user loyalty and brand recognition while gaining operational control and the ability to integrate advertising and data analytics across platforms.

Microsoft’s investment in Uber represents an affiliate relationship, where Microsoft holds a minority stake that provides exposure to the ride-sharing industry and opportunities for technology collaboration without requiring Microsoft to consolidate Uber’s financial results or maintain operational control. This affiliate structure allowed Microsoft to participate in Uber’s growth while maintaining its focus on software and cloud services.

Ford’s historical relationship with Mazda exemplifies how affiliate structures can evolve. Ford held a 25% stake in Mazda beginning in 1979, providing influence over Mazda’s operations and access to Asian automotive markets while allowing Mazda to maintain its independent brand identity and operational autonomy. Over time, Ford increased its stake to 33%, strengthening the partnership, before eventually divesting its ownership in 2015.

| Aspect | Affiliate Associates | Subsidiary Companies |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership Level | Minority stake (20-50%) | Majority or full ownership (>50%) |

| Control | Influence only, no unilateral control | Full operational control |

| Financial Consolidation | Separate financial statements, equity accounting | Consolidated financial statements |

| Legal Liability | Limited to investment amount | Limited to investment amount (with exceptions) |

| Decision Making | Requires consensus among shareholders | Parent company can make unilateral decisions |

| Tax Treatment | Separate tax returns | Can file consolidated returns |

| Operational Independence | High degree of independence | Subject to parent company direction |

| Board Representation | May have board seat but minority voice | Can elect majority of board |

| Strategic Alignment | Collaborative, negotiated alignment | Direct parent company control |

| Reporting Requirements | Equity method accounting | Full consolidation with intercompany eliminations |

The decision to structure an investment as a subsidiary or affiliate depends on several factors. Companies typically choose subsidiary structures when they want to maintain operational control, pursue integrated strategies, or isolate high-risk operations. Subsidiaries are particularly valuable for international expansion, where local legal requirements may necessitate a separate legal entity, and for diversified conglomerates that want to maintain control over multiple business units while keeping them as separate entities for liability and tax purposes.

Companies typically choose affiliate structures when they want to maintain operational independence, share risk with other investors, or participate in joint ventures. Affiliate structures are valuable when the parent company lacks expertise in a particular industry or market and wants to benefit from other shareholders’ knowledge and experience. They are also valuable when the parent company wants to maintain a more passive investment role and allow the affiliate’s management team to make operational decisions without parent company interference.

The choice between these structures also depends on the parent company’s long-term intentions. If the parent company plans to eventually acquire full control of the investment, it might start with an affiliate structure and gradually increase its ownership stake over time, eventually converting the affiliate into a subsidiary. Conversely, if the parent company wants to maintain a long-term minority stake while allowing other shareholders to maintain control, an affiliate structure is more appropriate.

The differences between affiliate associates and subsidiary companies are substantial and have far-reaching implications for corporate structure, financial reporting, tax obligations, and operational management. Subsidiaries provide the parent company with control, consolidated financial reporting, and the ability to pursue integrated strategies, but they also require more complex financial reporting and compliance obligations. Affiliates provide the parent company with influence and participation in investment returns while maintaining operational independence and simpler financial reporting, but they limit the parent company’s ability to direct the affiliate’s operations.

Understanding these differences is essential for businesses planning expansion, managing investments, or restructuring their organizational hierarchy. The choice between subsidiary and affiliate structures should be made carefully, considering the parent company’s strategic objectives, the nature of the investment, tax implications, and the desired level of operational control. With proper planning and expert guidance, companies can structure their investments in ways that optimize financial performance, minimize tax obligations, and achieve their strategic objectives while managing risk effectively.

Whether you're managing affiliate associates or subsidiary relationships, Post Affiliate Pro provides comprehensive tracking, reporting, and management tools to optimize your affiliate program performance and maximize ROI.

Discover the main differences between affiliate marketing and advertising. Learn about performance-based vs direct advertising models, cost structures, and whic...

An Affiliate is a person or company that promotes another company's products or services to earn commissions. Learn how affiliate marketing works, its benefits,...

Discover the fundamental differences between affiliate marketing and traditional sales. Learn how affiliates leverage social proof and peer influence versus dir...

Cookie Consent

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience and analyze our traffic. See our privacy policy.